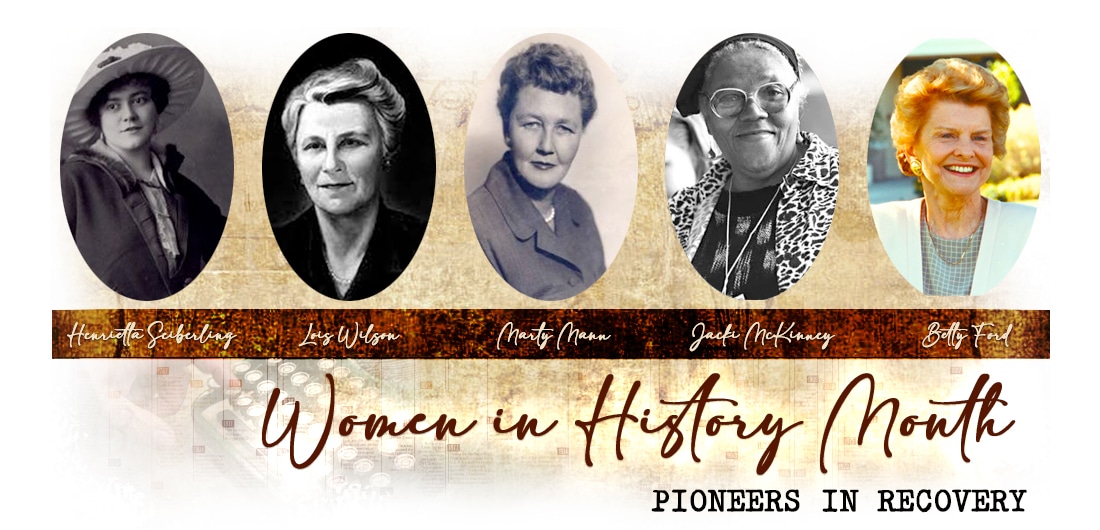

Henrietta Seiberling

Henrietta Seiberling

Key “Non-Alcoholic” Figure in the Founding of Alcoholics Anonymous

When Alcoholics Anonymous wanted to mark its birthplace, it looked to the gatehouse of Stan Hywet in Akron. It was there that the two best-known characters in the Alcoholics Anonymous movement — Dr. Bob Smith and Bill Wilson — first met. But there was another person present; Henrietta Buckler Seiberling arranged the meeting, helped nurture the early organization and ever reminded the AA leaders of the need for a strong spiritual under pining for an alcoholic’s recovery.

Seiberling was satisfied to work in the background. The social customs of the day, her background as well as the background of her husband, explained why she opted to play such a role.

Henrietta Buckler was born in Lawrenceburg, Ky., on March 18, 1888. She was reared in Texas where her father, Julius Augustus Buckler, was a judge of the Common Pleas Court. She was well educated, graduating from Vassar College, when she was only 15. She majored in music, ideal for the well-bred lady of the day. In 1917, she married John Fredrick Seiberling, eldest son of Akron industrialist F. A. Seiberling.

Seiberling was not an alcoholic; she was, however, involved with the Oxford Movement, an evangelical fellowship of intellectuals who believed in the responsibility of Christians to solve social problems. Seiberling helped organize the group’s “alcoholic squad” in Akron.

Dr. Bob Smith and his wife came into the Akron Oxford Group. A physician, Smith was an alcoholic. Aware of his drinking problem, Seiberling invited the Smiths over for a small meeting of the Oxford Group. Members shared their deepest secrets and then Smith admitted for the first time that he was a “secret drinker and I can’t stop.” The group then prayed together.

The Oxford Movement was not peculiar to Akron. It had groups in many cities throughout the United States and Europe. The Oxford Movement was also a kind of network. Members often contacted others in other cities. It was through this network that Seiberling met Bill Wilson, a stockbroker from New York in Akron on business. Wilson was also a recovering alcoholic. Wilson told Seiberling that he had had a religious experience and found the strength to stop drinking.

Seiberling quickly arranged a meeting between Wilson and Smith. The two worked together to support each other as they dealt with alcoholism. Working with Seiberling, they also came up with many of the tenets that still mark Alcoholics Anonymous — never to drink again, to lead a spiritual life and to share their experiences with others. Initially working through Akron’s Oxford Group, Alcoholics Anonymous soon struck out on its own, meeting at the old King School. Bill Wilson acted as the group’s promoter; “Dr. Bob” was the “homeyness” that the alcoholics needed at the beginning, Seiberling recalled.

Seiberling contributed much of her time, resources, and home to the ongoing work of Dr. Bob and Bill W. Her contributions to the very early days and meeting of Dr. Bob and Bill W. in Akron, Ohio are considered nothing less than a miraculous “keystone” of human compassion, spiritual fortitude, and care…which was instrumental in the movement taking shape as it did.

Lois Wilson

Lois Wilson

Co-Founder of Al-Anon

(An excerpt from Lois, speaking on “co-dependence addiction” and her recovery).

“We had the house full of drunks in all stages of sobriety. It seemed to me he was trying to dry out all the drunks in the world.

We gratefully went to meetings of the fellowship to which our hopeful friend belonged, and Bill used their half-dozen spiritual principles in his work with alcoholics. Later, he wrote the A.A. book, he expanded the number to Twelve Steps so as to be sure there were no loopholes through which a drunk could escape.

After a while I began to wonder why I was not as happy as I ought to be, since the one thing I had been yearning for all my married life had come to pass. Then one Sunday, Bill asked me if I was ready to go to the meeting with him. To my own astonishment as well as his, I burst forth with, “Damn you old meetings!” and threw a shoe as hard as I could.

This surprising display of temper over nothing pulled me up short and made me start to analyze my own attitudes. By degrees I saw that I had been wallowing in self-pity, that I resented the fact that Bill and I never spend any time together any more, and that I was left alone while he was off somewhere scouting up new drunks or working with old ones. I felt on the outside of a very tight little clique of alcoholics that no mere wife could enter. My pride was hurt by the fact that friend, another alcoholic, had been able to do for Bill in a short time what I had tried and failed to do all our married years.

My life’s purpose of sobering up Bill, which had made me feel desperately needed, had vanished. I sought something to fill the void. As I began to be honest with myself, I recognized how greatly Bill had developed spiritually and how necessary to his sobriety was his feverish activity with alcoholics. I decided to strive for my own spiritual growth. I used the same principles as he did to learn how to change my attitudes.

Several years later, Bill and I found that strained relations such as ours often developed in families after the first starry-eyed period of sobriety was over. We were heartsick and puzzled to discover that, though alcoholics were recovering through this wonderful new program, their home lives were often difficult. We began to learn how many adjustments had to made and that the partner of the alcoholic also needed to live by a spiritual program.

Soon, small groups composed of the family members of alcoholics in A.A. sprang up all over the country. They had a threefold purpose: to grow spiritually through living by the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous; to give encouragement and understanding to the alcoholic in the home; and to welcome and give comfort to the families of new or prospective A.A. members.

Today Al-Anon groups have spread over this country, Canada, and many other lands. Many agencies, too, recognize that alcoholism is a family problem and that recovery can be greatly hastened by family understanding.”

How Al-Anon Works for Families & Friends of Alcoholics, Al-Anon Family Group Headquarters, Inc. 1995, 2008, pp. 152-159

Marty Mann

Marty Mann

Founder – National Committee for Education on Alcoholism (Known as the NCAAD today)

Marty Mann was an early proponent of treating substance use disorders as a public health issue, recognizing that substance use disorders are a disease—not a moral failing.

Marty worked as a magazine editor, art critic, and photojournalist for renowned magazines such as Vogue, Harpers, and Tattler. However, she had an alcohol use disorder – and it progressed to the point where she was no longer able to hold a job, drifting in and out of homelessness while living abroad in London. In 1936, she returned to her family in the United States and sought help from doctors.

Even though she began a successful path to recovery as one of the first women to join AA, Marty found that other women were often reluctant to seek help. At the time, many people believed that alcohol use disorder among women was caused by underlying psychiatric problems, and that alcohol use problems were more pathological among women than among men.

In 1944, with funding from the Yale Center on Alcohol Studies, Marty founded the National Committee for Education on Alcoholism (NCEA) to reduce stigma and help people get the treatment they needed. A main tenet of the organization’s mission was that alcoholism is a public health problem, and therefore a public responsibility. Marty credited her life partner, Priscilla Peck, with encouraging her to write the book, Primer on Alcoholism, and with helping her conceptualize the NCEA. Today this organization is called the National Council on Alcohol and Drug Dependence (NCAAD) and has expanded its work to include other substance use disorders.

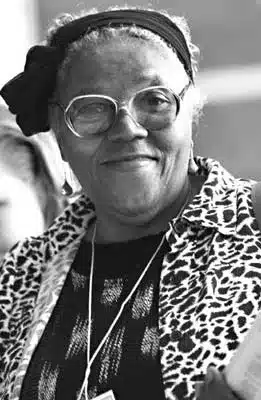

Jacki McKinney, M.S.W.

Jacki McKinney, M.S.W.

Mental Health & Substance Use Disorder Advocate and Care Provider

Jacki McKinney was an activist and social advocate for survivors of trauma. McKinney was born in New Jersey on October 18th, 1934, from a very young age as early as two years old she was abused by her father beginning a cycle of trauma she dealt with over the next 50 years of her life.

As a child she had difficulties expressing what was really going on in addition to being punished or ignored if she tried. Her limitations around her continued suffering due to abuse led to her expressing more physical symptoms of illness than the emotionally illness she was experiencing.

Overwhelmed by the constant abuse by the age of nine years old she had stopped walking. McKinney’s physical display of ailment ended up getting her put in a home for disabled children. Unfortunately, the home for disabled children was just as traumatic. The facility housed all White staff and patients in addition to acting as housing for children suffering from the contagious disease, polio.

An 11 year old McKinney returned home no longer fueled by fear and confusion but instead a rage that grew from the knowledge of her truth.

This rage stayed with her for the next 40 years of her life. As she continued to experience traumas through her life, she stated in an interview that “I was victimized again in the streets of New York by a serial rapist along with a lot of other women who seemingly got over it. But I didn’t. And because of my background, my history and lack of treatment I had a major break. My mama would call it a break down but it was a break up and I ended up living homeless in the streets walking away from the family, walking away from my husband, walking away from my house, my life and I never regained those things but I did regain my family.”

This break led her to becoming homeless on the streets of Washington DC which is where she met two women with the D.C. Rape Crisis Center who help get her back on her feet and involved with advocacy and activism.

She then went on to join the Consumer Movement in New York to focus on the mental health industry. Her first role in activism was in welfare rights fighting for the rights of other women and other mothers, which she said was the first time in her life something had been dealt with as a woman and a mother in a positive way. She then joined a program called New Careers for the Poor. New York was one of the demonstration states so she was recruited to go to school and to go to work. From that experience she went on to go to get a GED and then to go on to college.

From there she went on to join the Consumer Movement in Philadelphia becoming the Director of the first consumer operating service program, a case management unit. All the people in the unit were people who were consumers (patients) of mental health making the case management program the most radical program made to date because it was also the first to use current mental patients on the professional team. All of them were people of color and they felt it was vital to the program that they had people who could connect with the patient they were trying to serve. The program was part of a research demonstration funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the first government funded peer support group. At the same time Jacki also attended her first Alternative conference, which is where consumers get together and share ideas and present programs. Opening Jacki’s eyes to more ways to get involved.

She stated in an interview “the biggest piece I brought to that study was do not study the women without studying their children because my children lived lives of hell because I lived a life of hell.” a fact many know too well. Soon after her time with the study she began to be a national spokesperson for the issue of trauma. She had three main goals as a spokesperson. The first was to develop a policy against seclusion and restraint. The second was to spread the knowledge that if you don’t treat the children when you’re treating the mother, then you’re creating the second generation of the same issue. The third was to inform that battered women make up a large portion of the prison recurring recidivism rates.

That epitomized Jacki’s philosophy and showcased the reason she went on to become a recipient of Mental Health America’s highest honor, the Clifford W. Beers award, presented to a consumer of mental health and/or substance abuse services who best reflects the example set by Beers in his efforts to improve conditions for, and attitudes toward, people with mental illnesses.

She is the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration’s Voice Awards program which was presented to her for her distinguished leadership and advocacy on behalf of trauma survivors.

Source: (https://rightsandrecovery.org/e-news-bulletins/2021/10/18/in-honor-and-memory-of-jacki-mckinney/)

Betty Ford

Betty Ford

Former First Lady, Founder of the Betty Ford Addiction Center, and Bold Voice for “De-stigmatizing” Addiction

In April 1978, Betty Ford announced that she had an addiction to prescription medication, and would be seeking treatment for that addiction. Later that month, the former first lady disclosed that she was also struggling with and receiving treatment for alcoholism—something she had only been able to admit to herself after spending some time in rehab.

With the help of medical experts, Betty’s family and friends organized an intervention—a fairly new concept at the time—for her in April 1978. After the intervention, Betty agreed to enter a rehabilitation program at the Long Beach Naval Hospital. The hospital had started its rehab program a few years before to treat Naval service members and their dependents. (Gerald Ford served in the Navy during World War II.)

Rehab “was a rude awakening for her,” McCubbin says. Betty was public about the fact that she was entering rehab for doctor-prescribed medication; but at the beginning, she didn’t agree that she had a problem with alcohol. Within a couple of weeks in the program, she was able to admit—both to herself and the public—that she was an alcoholic.

Betty Ford’s public candor around her addiction mirrored the way she had handled her breast cancer diagnosis and radical mastectomy in 1974. Women wrote her letters thanking her for talking about the disease publicly, and her experience motivated many women to perform self-exams or receive medical checks for breast cancer.

Betty’s public struggles with pills and alcohol brought attention to addiction issues, and highlighted the fact that substance abuse was a problem for women as well as men. A year after her own intervention, she participated in one for her friend and neighbor, Leonard Firestone, retired president of Firestone Tire & Rubber Company. Firestone entered rehab, and when he got out, he convinced Betty that they should open their own rehab center.

At first, Betty wasn’t sure she wanted to attach her name to a rehab center, fearing that it would be embarrassing for her if she relapsed, McCubbin says. But she went ahead with it, founding the Betty Ford Center with Leonard Firestone and the physician James West in 1982.

Betty, who died in 2011, was very active at the center. She visited and talked with patients, and established a rule that the center could not disclose the identity of anyone staying there. And, at a time when most people who sought rehab were men, she mandated that the Betty Ford Center always keep enough beds available for women as well, acknowledging the reality that women struggle with addiction and deserve to have a place to go for treatment.

Source: (https://www.biography.com/activists/betty-ford-addiction-alcoholism-center)